Artists

Rasheedah Phillips

She // Her // Hers

They // Them // Theirs

Interdisciplinary Artist and Experimental Writer

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Rasheedah Phillips is a queer housing advocate, parent, writer, interdisciplinary artist, and cultural producer who uses web-based projects, zines, short film, archival practices, experimental nonfiction, speculative fiction, printmaking, performance, social practice, installation, and creative research to explore the construct of time, temporalities, and community futurisms through a Black futurist cultural lens and experience. Phillips's writing and artwork has appeared in The Funambulist Magazine, e-flux Architecture, Flash Art Magazine, Philadelphia Inquirer, Recess Arts, and more. Phillips is the founder of The AfroFuturist Affair, founding member of Metropolarity Queer Speculative Fiction Collective, cofounder of Black Quantum Futurism, cocreator of the award-winning Community Futures Lab, and creator of the Black Women Temporal Portal and Black Time Belt projects. Recognized as a national expert in housing policy, Phillips is a 2016 graduate of the Shriver Center Racial Justice Institute, a 2018 Atlantic Fellow for Racial Equity, and a 2021 PolicyLink Ambassador for Health Equity. As part of Black Quantum Futurism and as a solo artist, Phillips has been awarded an Arts at CERN Residency, a Vera List Center Fellowship, A Blade of Grass Fellowship, a Velocity Fund Fellowship, among others. Phillips has exhibited, presented at, been in residence, and performed at the Institute of Contemporary Art London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Serpentine Gallery, Red Bull Arts, the Chicago Architecture Biennial, Akademie Solitude, Manifesta 13 Biennale, documenta fifteen, and more.

Donor -This award was generously supported by Katie Weitz, PhD.

This artist page was last updated on: 07.12.2024

Essay by Rasheedah Phillips. Originally published in Critical Analysis of Law, 2022.

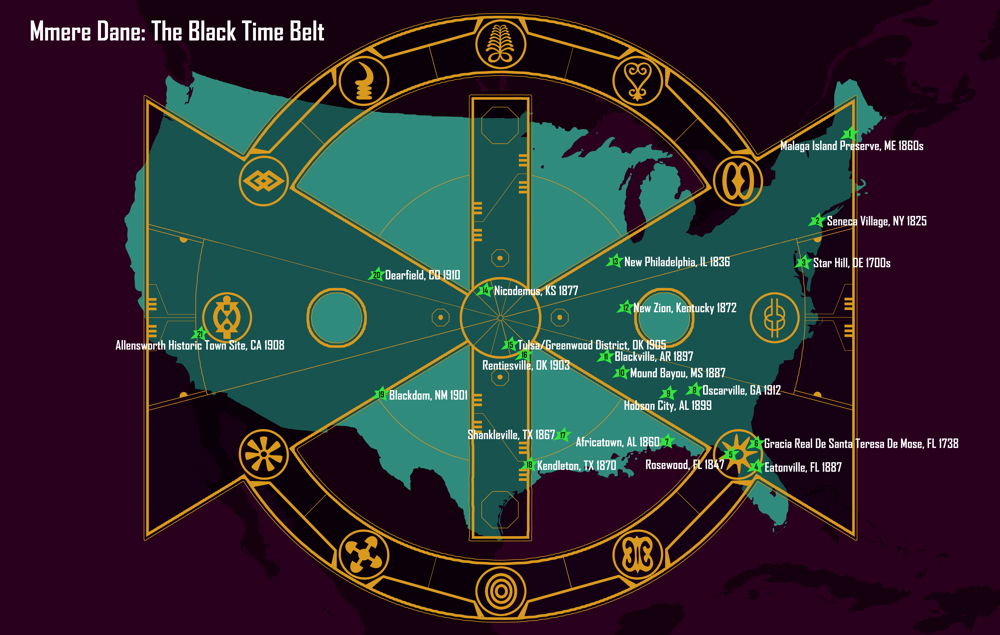

Mmere Dane: Black Time Belt by Rasheedah Phillips, 2021. Digital, web.

Image courtesy of the artist.

The Prime Meridian Unconference by Rasheedah Phillips, 2020–2022. From the Time Zone Protocols exhibition and digital space. Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New York.

Photo by Argenis Apolinario, courtesy the Vera List Center for Art and Politics.