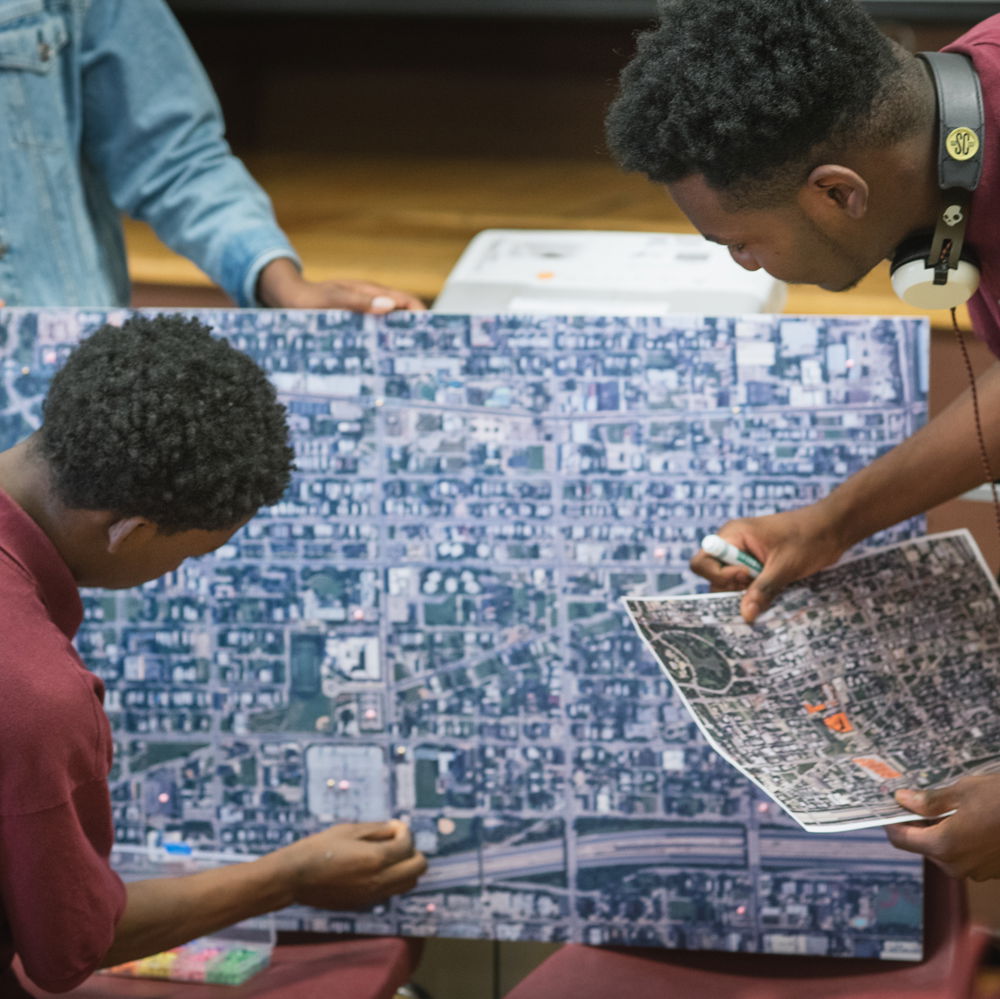

Leah Wulfman: Opening Up Conversations

Architect Leah Wulfman on prototypes and building a classroom for the future

Young Architect's Program by Leah Wulfman, 2025. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

As a mixed reality architect, Leah Wulfman's practice encompasses multidisciplinary design, education, and game development. Throughout their practice, they strive to create discussion and forefront ways of working that are distributed, embodied, and collaborative. In the following conversation, they share what it means to be a Carrier Bag architect, how they came into architecture, and how they subvert traditional modes of presentation.

Jessica Gomez Ferrer: What does it mean to be a Carrier Bag architect?

Leah Wulfman: “Carrier bag” comes from Ursula K. Le Guin, the feminist sci-fi author who wrote an essay called “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” In it, she's proposing an alternative origin and emphasis for storytelling and writing, one that resists the traditional hero’s journey. There's the hero's journey, which we see in film, video games, and kind of everywhere, even in politics. So, it's an anti-hero storytelling method, in relation to technology, design, and especially architecture, which historically has been so centered around individual egos or masters.

For me, being a Carrier Bag architect and designer is multifaceted because, foundationally, it rejects the idea of a singular ego that's centered in the way that I'm working. It’s a process-oriented approach that values prototypes over projects. In architecture, people often talk about projects — and having a “Project” — less so architectural prototypes, and rarely prototypes in general. Prototypes, while often directed and embedded with specified goals and functions, are open-ended, collaborative, and cumulative — passing through many hands and bodyminds, with insights gained along the way. My work is oriented around ways of thinking, working, and being in the world that are not top-down but distributed, embodied, and collaborative.

So in terms of prototypes, there is purposeful alignment with more open-source methods of making and working rather than proprietary ones. I’m less interested in positioning a single author at the center of the work, and more invested in creating opportunities for anyone — with varying ages, backgrounds, expertises — to engage with the work.

In “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Le Guin speaks to hunter-gatherer society and emphasizes the act of gathering as a means of collecting, experiencing, and sharing, and as a central approach to story making and telling. We don’t have to orient ourselves around heroes, linear stories, and singular achievements. We don’t need to go out into the world, kill or conquer something, and return home with that story. Instead, the way we share, in story and in living, is like putting things into a bag: a form of collecting and connecting, a literal and metaphorical “carrier bag.” As tools and technologies, bags and stories hold things. And a bag can take so many forms: it can be a pocket; it can be a folder on your desktop; it can be a cabinet; a space; it can be architecture. That's why I started calling myself a Carrier Bag architect.

A major impetus for this idea of the Carrier Bag also came from seeing Ian Cheng’s work Emissaries in early 2017, after which he developed the artificial lifeform BOB (Bag Of Beliefs). Ian works with video games and live simulations as emergent systems, where characters and stories are governed by dynamic rule sets rather than linear narratives. His work feels like a thinking brain, a complex, spatial, and continuously evolving experience, which despite being entirely screen-based is embodied and architectural.

Discordant Whole by Leah Wulfman and Adam Miller, 2022. Liberty Research Annex, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Photo courtesy of Leah Wulfman.

Jessica: I want to zoom out for a second and ask, how did you become interested in architecture?

Leah: Well, it's funny, because I think I always was. I've always been a spatial thinker, and I've always been drawn to storytelling, as it relates to materials and temporality, and what is more architectural than that? So I would say I've always been interested in architecture; I just didn't know architecture. I loved math and excelled in art — I took woodworking every year that I could in high school, which I absolutely loved — and I was clearly a spatial thinker at my core. Calculus came naturally to me, as if it were already ingrained in my body, because of all the ways it operates spatially. But after my teacher told me I should look into architecture, I took a drafting class in high school, and I dropped it after a week. It felt mechanical, not at all spatial, and disconnected from the things I was interested in, so I far too quickly dismissed architecture as a path. No one told me or enlightened me on what it actually was, so despite my obsessions, I was pretty dissuaded from seeing it as even an option.

I originally went to school for math. When I first got to college, I was one of three female-bodied students in the Honors Mathematics program. Interestingly enough, I remember while I was taking a Real Analysis class, I started going on these really wandering walks and would find myself in different parts of Pittsburgh. Wherever I ended up, I would just sit and do my math there. But I believe I still really yearned for a sort of studio practice. In terms of making and actually materializing my experiences and insights, as it relates to my being in the world, I really missed it. So, in a way, I was reenacting this mode of being by going on these walks.

Because of my relationship to woodworking, I found myself working on a bamboo bicycle in the school woodshop around the time first-year architecture students were coming through. One of their first projects was to laminate different pieces of wood and then think about them in terms of composition and tool operations. It was really fascinating to see people churning something through a bandsaw, but then talking conceptually and spatially about them. I loved it. So I inquired, "Do I take classes? Is it a self-defined major? Is it a BXA, an intercollege degree crossing some form of art with some form of science?” Fairly quickly, the academic advisor said, "Well, all the classes you want to take are in architecture."

I started in architecture partly because it seemed like the natural next step, but I didn’t grow up thinking that. I grew up in a very rural area, and, like in many places in the United States, there was not much of a lexicon around architecture and the buildings and spaces that we inhabit. And I found that when I went to school, people came from wealthy families so they had traveled and seen architecture or what they were specifically told was architecture, or had someone in the family or nearby who was an architect. Or they were from countries where architecture is more culturally embedded. For a few others, video games served as their introduction to architecture, which is now increasingly common. One of my good friends from school, Tom, played RollerCoaster Tycoon. It’s interesting how people find their “ins,” but for the most part, I didn't have those typical ins, and I literally had to have it hit me over the head that this was the path for me, which in some ways is pretty common for me. Things have to be worked through and felt in my body first, before they fully enter my head.

“Things have to be worked through and felt in my body first, before they fully enter my head.”

Jessica: What rules or conventions in the field do you delight in breaking?

Leah: Typically, in architectural practice — and within architecture education and academia — there’s this ever recurring ritual: a person stands in front next to their work and explains it. Students and professionals spend hours making perfected, beautiful drawings. They don’t sleep, they show up, and then are asked to stand up and perform this song and dance in front of their work. Someone on a jury waves their hand around in the direction of the work, while saying some things from a seated position, and typically each person in the ring of jury members does this, and that’s mostly it. That’s normalized and treated as doctrine, despite the certain factions of intellectualism and existing hierarchies that get foregrounded and perpetuated, but largely remain unquestioned.

As a student, I became sick of solely working on hypothetical projects. I understood the function of them. I understand the purpose and need to practice designing buildings through hypothetical project proposals, working through details and expressing ideas through drawing. It's not like you can just automatically make the leap into constructing a building. But I wanted to find more immediate, tangible and ready-made ways for people to experience the architecture without relying on a formal presentation, without prompting presentation as architectural experience and expression. So I was looking for various and more immediate ways for people to experience my architectural designs without requiring a formal presentation, with me standing in front of it narrating the narrative and walk-through. That's actually how I got into interactive, spatial media in general.

There’s a barrier to entry built into the way architecture is talked about and presented — the language, the format, the way we platform and preface the work itself. These conventions reinforce a kind of performative expertise that limits who feels permitted to engage and undermines any sense of shared agency. I wanted to remove some of those barriers and begin to develop experiences people could simply step into and would invite participation and direct feedback. Around my third and fourth year of college, that became key for me. I wanted anyone to just come in and be able to get it without the extra fluff and any performative introduction. And I wanted to be able to, say, have a small child enter, be able to grasp the work through their eyes, and then we could have a conversation. I wanted to not preface the work, but to have the work preface itself, and then have conversations. That was a big moment for me.

My first full VR work embodied this, and included a prototype where you swam through an intricate cave space I had designed. Everyone, whether they knew how to swim or not, had the concept of what swimming is. You do a swimstroke in one direction, and you move in that direction. If your head is facing in that direction, you're going to go in that direction. Very intuitively, we could move through space in a way where there weren’t all these awkward contraptions and disembodied teleportation mechanics. This meant that a six-year-old and an eighty-one-year-old, who had never been in VR before, could get into the work and move through it. I wanted to hold those experiences really dear to me and question who’s an expert, for what and why. I wanted to rid the barrier to entry and those questions of hierarchy, which I think get in the way of conversation versus opening up conversation.

Young Architect's Program by Leah Wulfman, 2024. Materials & Applications, Los Angeles, CA.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jessica: Could you talk a little bit about the work that's included in the exhibition after school at the Heinz Architectural Center?

Leah: after school looks at the histories, presents, and futures of public education in the United States, while also pulling from the Carnegie Museum’s collection. Pittsburgh, in many ways, was a convergence point, being home to a group of patriarchal industrialists and benefactors who helped found and fund the Museum, and an epicenter for shaping what we now recognize as the American public education system, one that’s been exported globally. We’re at a critical juncture now, as public education continues to be disinvested in and eclipsed by private and charter institutions. I think twelve public schools are closing in Pittsburgh this year alone. The exhibition begins with that premise.

The curators tasked me with considering what a “classroom of the future” could be. For me, that doesn’t mean a classroom defined by rigid order or predictable problem-and-answer structures and solutions to things. It’s a space that’s fluid, iterative, and open to redefinition.

My piece is an embodied, iterative drawing game played out and onto a series of sealed inflatables. You can think of these inflatables almost as a deconstructed bounce house, with the different components arranged throughout the gallery space. The game is projection-mapped onto these inflatables: when someone draws on paper, their marks are projected into the space, creating a direct correlation between the drawn forms and how they appear on the architectural, spatial play set.

There's constant movement in the space and people finding ways that their body inhabits it, which isn't just sitting in a hard chair in a row. There's different ways, whether we talk about people who are disabled, or neurodivergent, or coming from varying experiences and backgrounds in their life and day. The piece makes space for having multiple perspectives and approaches, and maybe within the soft space of the class, you could move ten times to find different ways of thinking through something, whether individually or together.

I believe that there should be after-school or in-school education, especially at the primary school level, around architecture. And that could also be in relationship to what we think of as civic courses or experiences, as a point of collective dreaming and responsibility. A big part of my thinking comes from working in youth programming, bringing students to museums. They were able to tease out motifs and themes in the artwork far more openly and perceptively than most adults. Their insights are pretty profound and unfiltered. They have insights that haven't been taken away from them, whether through formal education, or familial or societal pressures or whatever. There's an openness. But then they go home and they feel that they don't have agency, or a sense of contribution to the built environment around them, their neighborhoods, homes, spaces, the buildings, the architecture, or the community, spatially and materially. And I think this is so profoundly problematic. I think it actually speaks to a lot of where we're at as a society, but it also even speaks to me, as someone who makes and plays video games, where they can have that agency in terms of creating an avatar, and making space in video games, whether it be Roblox or Minecraft or what have you. They have that sense of creative liberty, and agency, but it often only exists digitally and remains virtually.

So I was like, "I want to create a space where we collectively consider and imagine through what these forms are, the way we can image them, the way we can draw them." That profile to me might look like a chimney with smoke, but for you, it has balloons spilling out the top. Or it might be weeping, crying water. It's a windmill. Or it has four windows, and there's a cat in one of them. And so it's a way of thinking beyond givens, beyond constraints, beyond what we think of as normative building and architecture, and saying, "Yeah, but what if."

I worked with then five-year-old, Jin Meisenberg, on a back-and-forth drawing exercise that initiated the project. She would add into the forms I was drawing and then begin to describe them: “Oh, this is the thinnest, thinnest building ever.” We’d continue to draw and ask, “Well, what is it?” and she’d say, “This is a water clock, and this is where they make rainbows.” Can you imagine if we talked this way every day? If we didn’t just sit around twiddling our thumbs and assuming that everything has to be exactly as it is?

Again, it’s about creating a way to open up conversations. It’s a platform, like a classroom, that is a microcosm of a way that we can practice spatial thinking and iteration in a way that's truly engaged and is iterative. No one person is in control. You might learn from someone else, which might lead to you being more inclined to learn from your neighbors, and adopt a mindset of reciprocity through collective iteration.

“I believe that there should be after-school or in-school education, especially at the primary school level, around architecture.”

Jessica: I love that interactivity. I've seen photos of those inflatables and they look so fun. I love that you're bringing this playfulness into a typically austere space.

Leah: It's so fun. The space and inflatables get completely undone and then everything needs to be tidied up at the end of the day. There’s always this question of maintenance generally falling on someone else, and I think primary school classrooms and playgrounds embody a similar idea: you make a mess, you have fun, you learn, and then you learn to put things away. You learn to create that together. I’d love to see more of that approach.

I think people have a lot of fun when everything gets misaligned, matched and mismatched, and placed again. Projection mapping is often all about perfected alignment, but then over the course of people interacting with it, the projections start to spill onto others, creating this strange, unexpected remix. Through misalignment and realignment, variations and iterations are drawn in space. Every moment offers a new and different insight into agency. Of course, things reset maybe at the end of the day, or at the end of the week, starting fresh again, but I love the playfulness of it. There have even been kids who have just picked up these massive inflatables and thrown them across the room!

Jessica: My last question for you is a little different: what has the USA Fellowship afforded you?

Leah: Oh, many things. I would say a sense of stability. A moment, even to foreground the work. I was able to work on that project over the summer, in part because I had this award. As someone who has a progressive disability, to have a semblance of a foundation is probably the most massive thing. It's afforded me a stability and flexibility with my work and life that I wouldn't otherwise have been afforded without a ton of work. And I needed a break too. So it has also afforded me rest. I'm happy and feel really fortunate to be able to have that.

Related artists

-

Leah Wulfman

Mixed Reality Architect, (Multidisciplinary Designer, Educator, Mixed Reality Game Developer)